KYIV — Many U.S.-made satellite-guided ammunitions in Ukraine have failed to withstand Russian jamming technology, prompting Kyiv to stop using certain types of Western-provided armaments after effectiveness rates plummeted, according to senior Ukrainian military officials and confidential internal Ukrainian assessments obtained by The Washington Post.

Russian jamming leaves some high-tech U.S. weapons ineffective in Ukraine

Russia’s ability to combat the high-tech munitions has far-reaching implications for Ukraine and its Western supporters — potentially providing a blueprint for adversaries such as China and Iran — and it is a key reason Moscow’s forces have regained the initiative and are advancing on the battlefield.

The success rate for the U.S.-designed Excalibur shells, for example, fell sharply over a period of months — to less than 10 percent hitting their targets — before Ukraine’s military abandoned them last year, according to the confidential Ukrainian assessments.

While other news accounts have described Russia’s superior electronic warfare capabilities, the documents obtained by The Post include previously unreported details on the extent to which Russian jamming has thwarted Western weaponry.

“The Excalibur technology in existing versions has lost its potential,” the assessments found, adding that battlefield experience in Ukraine had disproved its reputation as a “one shot, one target” weapon — at least until the Pentagon and U.S. manufacturers address the issue.

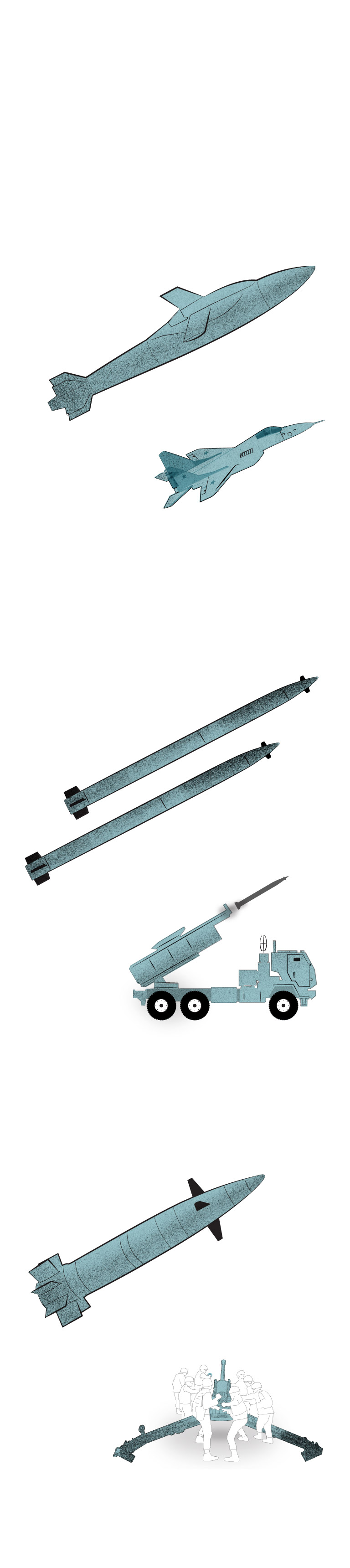

Some of the weapons

affected by Russian jamming

Joint Direct Attack

Munition-Extended Range

Air-launched GPS-guided weapon that converts dumb bombs into precision-guided glide bombs.

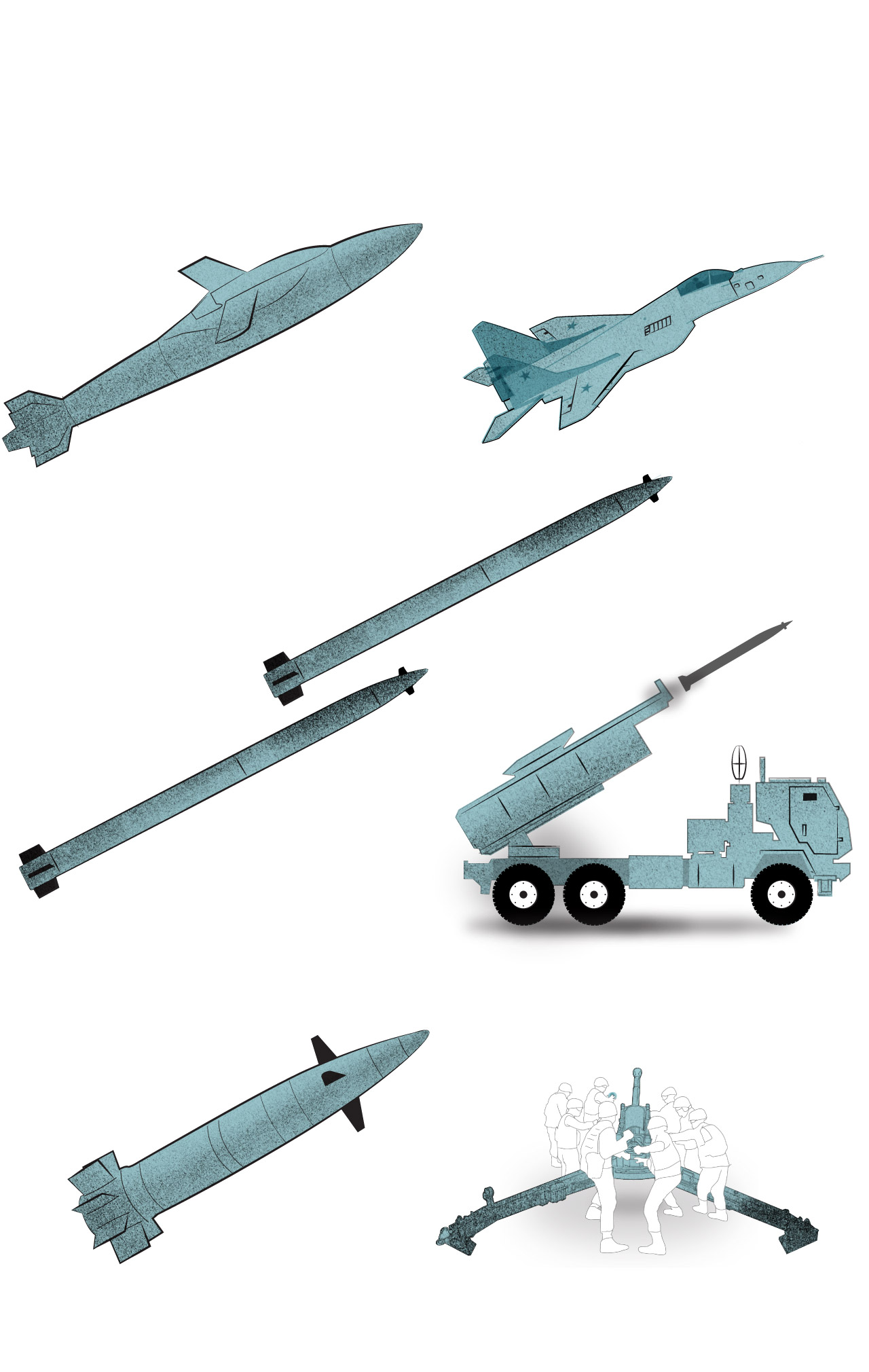

Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System

The M142 (pictured) and M270 launch rockets at a range of about 50 miles. They can also fire the longer range ATACMS missiles.

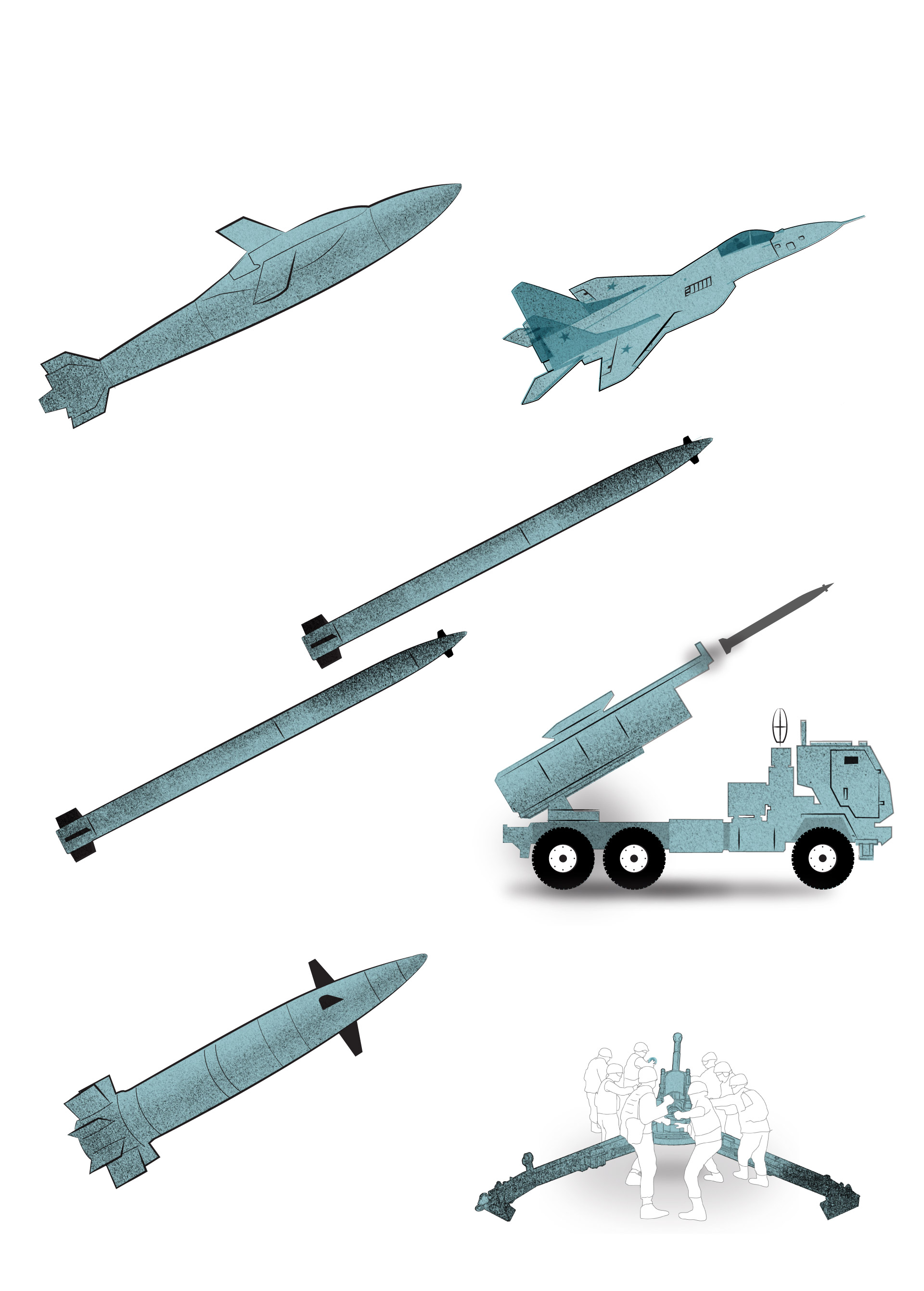

Rounds are guided by GPS coordinates programmed before firing. NATO 155mm howitzers such as the M777 fire the weapon.

Note: Illustrations not to scale

Sources: Raytheon, Army Recognition

Some of the weapons

affected by Russian jamming

Joint Direct Attack

Munition-Extended Range

Air-launched GPS-guided weapon that converts dumb bombs into precision-guided glide bombs.

Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System

The M142 (pictured) and M270 launch rockets at a range of about 50 miles. They can also fire the longer range ATACMS missiles.

Rounds are guided by GPS coordinates programmed before firing. NATO 155mm howitzers such as the M777 fire the weapon.

Note: Illustrations not to scale

Sources: Raytheon, Army Recognition

Some of the weapons affected by Russian jamming

Joint Direct Attack Munition-Extended Range

Air-launched GPS-guided weapon that converts dumb bombs into precision-guided glide bombs.

Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System

The M142 (pictured) and M270 launch rockets at a range of about 50 miles. They can also fire the longer range ATACMS missiles.

Rounds are guided by GPS coordinates programmed before firing. NATO 155mm howitzers such as the M777 fire the weapon.

Note: Illustrations not to scale

Sources: Raytheon, Army Recognition

Some of the weapons affected by Russian jamming

Joint Direct Attack

Munition-Extended Range

Air-launched GPS-guided weapon that converts dumb bombs into precision-guided glide bombs.

Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System

The M142 (pictured) and M270 launch rockets at a range of about 50 miles. They can also fire the longer range ATACMS missiles.

Rounds are guided by GPS coordinates programmed before firing. NATO 155mm howitzers such as the M777 fire the weapon.

Note: Illustrations not to scale

Sources: Raytheon, Army Recognition

Six months ago, after Ukrainians reported the issue, Washington simply stopped providing Excalibur shells because of the high failure rate, the Ukrainian officials said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive security matter. In other cases, such as aircraft-dropped bombs called JDAMs, the manufacturer provided a patch and Ukraine continues to use them.

Ukraine’s military command prepared the reports between fall 2023 and April 2024 and shared them with the U.S. and other supporters, hoping to develop solutions and open up direct contact with weapons manufacturers. In interviews, Ukrainian officials described an overly bureaucratic process that they said had complicated a path toward urgently needed adjustments to improve the failing weaponry.

The officials agreed to answer questions about the assessments in hopes of drawing attention to the Ukrainian military’s needs. Several Ukrainian and U.S. officials interviewed for this story spoke on the condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the issue.

The Pentagon anticipated that some precision-guided munitions would be defeated by Russian electronic warfare and has worked with Ukraine to hone tactics and techniques, a senior U.S. defense official said.

Russia “has continued to expand their use of electronic warfare,” the senior U.S. official said. “And we continue to evolve and make sure that Ukraine has the capabilities they need to be effective.”

The U.S. defense official rejected claims that bureaucracy has slowed the response. The Pentagon and weapons manufacturers have provided solutions sometimes within hours or days, the official said, but did not provide examples.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense, in a statement, said that it cooperates regularly with the Pentagon and also communicates directly with weapons manufacturers.

“We work closely with the Pentagon on such matters. In the event of technical problems, we promptly inform our partners to take the necessary measures to solve them in a timely manner,” the ministry said. “Our partners from the USA and other Western countries provide constant support for our requests. In particular, we regularly receive recommendations to improve the equipment.”

U.S.-made guided munitions provided to Ukraine typically were successful when introduced, but often became less so as Russian forces adapted. Now, some arms once considered potent tools no longer provide an edge.

In a conventional war, the U.S. military might not face the same difficulties as Ukraine because it has a more advanced air force and robust electronic countermeasures, but Russia’s capabilities nonetheless put heavy pressure on Washington and its NATO allies to continue innovating.

“I’m not saying no one was worried about it before, but now they’re starting to worry,” one senior Ukrainian military official said.

“As we share information with our partners and our partners share with us, the Russians definitely also share with China,” the official added. “And even if they don’t share with China … China monitors events in Ukraine.”

Failing to strike targets

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine created a modern testing ground for Western arms that had never been used against a foe with Moscow’s ability to jam GPS navigation.

Innovation is a feature of virtually every conflict, including the war in Ukraine, where each side deploys technology and novel changes to outfox the other and exploit vulnerabilities. The Russian military has been adept at electronic warfare for years, analysts and officials said, investing in systems that can overwhelm the signals and frequency of electronic components, such as GPS navigation, which helps guide some precision munitions to their targets.

Ukrainians initially found success using Excalibur 155mm rounds, with more than 50 percent accurately hitting their targets early last year, according to the confidential assessment, which was based on direct visual observations. Over the next several months, that dropped below 10 percent, with the assessment pointing to Russian GPS jamming as the culprit.

The study cautioned that far fewer shells were fired later in the research period, and many were not observed, leaving the precise success rate unclear.

But even before the United States ceased deliveries, Ukrainian artillerymen had largely stopped using Excalibur, the assessments said, because the shells are harder to use compared with standard howitzer rounds, requiring time-consuming special calculations and programming. Now they are shunned altogether, military personnel in the field said.

The senior Ukrainian official said Kyiv shared this feedback with Washington but got no response. The Ukrainians have faced a similar challenge with guided 155mm shells provided by other Western countries. Some employ guidance other than GPS, and it is unclear why they also became less effective. U.S. defense officials declined to address the Ukrainian assertion.

The Excalibur precision artillery round typifies many U.S. weapons: pricey and sophisticated but accurate. Ukraine has used the rounds, fired by U.S. artillery systems such as the M777, to destroy targets, like enemy artillery and armored vehicles, from about 15 to 24 miles away.

Rob Lee, a senior fellow with the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a Philadelphia-based research group, said that Russia’s use of electronic warfare to combat guided munitions was an important battlefield development in the past year. Many weapons are potent when they’re introduced, but they lose effectiveness over time, Lee said, part of a nonstop game of cat-and-mouse between adversaries who constantly adapt and innovate.

The involvement of defense companies is crucial to overcoming Russian defenses such as jamming, Lee said.

“The problem with a lot of Western defense companies,” Lee said, compared with Russian manufacturers, is that “there is not the same sense of urgency.”

A web of Russian electronic warfare systems and air defenses menace Ukrainian pilots, the documents said, adding that some Russian jammers also scramble the navigation system of planes. The Russian defense is so dense, the assessment found, that there are “no open windows for the Ukrainian pilots where they feel that they are not at gunpoint.”

Despite some effort to thwart the jamming, potential fixes seem limited until the West delivers F-16 fighter jets, the assessment found. Such modern planes would allow Ukraine’s air force to push Russian pilots back, enabling the use of different kinds of weapons with greater range and ability to avoid some electronic warfare systems.

The aircraft-dropped JDAMs provide another example of declining effectiveness of weaponry.

Their introduction, in February 2023, was a surprise to Russia. But within weeks, success rates dropped after “non resistance” to jamming was revealed, according to the assessment. In that period, bombs missed their targets from as little as 65 feet to about three-quarters of a mile.

Ukraine provided feedback about the jamming problem, and the U.S. and weapons manufacturers delivered improved systems in May, the documents said. Since then, JDAMs have proved more resistant to jamming than other GPS-guided weapons, the assessment found, and accuracy improved to a hit rate above 60 percent over nine months in 2023.

HIMARS were celebrated during the first year of Russia’s invasion for their success in striking ammunition depots and command points behind enemy lines.

But by the second year, “everything ended: the Russians deployed electronic warfare, disabled satellite signals, and HIMARS became completely ineffective,” a second senior Ukrainian military official said. “This ineffectiveness led to the point where a very expensive shell was used” increasingly to strike lower-priority targets.

The Ukrainian military documents did not assess guided M30 or M31 munitions, which are fired from HIMARS launchers. But in January, Ukraine’s military command wrote a policy paper urging Western supporters to provide an alternative: M26 cluster munitions that also could be launched from multiple-launch rocket systems. These low-tech, unguided rockets are resistant to jamming, and the cluster submunitions can still hit targets in a wide area even if the shot is imprecise.

Kyiv still considers its HIMARS rockets effective, but Russian jamming can cause them to miss a target by 50 feet or more.

“When it’s, for example, a pontoon bridge … but there’s a 10-meter deviation, it ends up in the water,” the first Ukrainian official said.

Russian jamming signals are sent up from the ground and form a cone-shaped area. Any guided munition — or aircraft — passing through is at risk of interference.

A battalion commander, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to do so publicly, described flying a reconnaissance drone in foggy conditions last year in Bakhmut to track a HIMARS strike on a Russian position. On his screen, the commander watched in dismay as each rocket missed.

One way the Ukrainians counter Russia’s jamming is by targeting known electronic warfare systems with drones before using HIMARS. This has proved effective in some cases.

“Initially, there were no problems,” the first senior official added. “It was simple: the machine arrived. The button was pressed and there was a precise hit. Now, it’s more complicated.”

The official added, “The Americans are equipping HIMARS with additional equipment to ensure good geolocation.”

One U.S. weapon used by aircraft, the GBU-39 small-diameter bomb, has proved resilient to jamming, according to the confidential documents. Nearly 90 percent of dropped bombs struck their target, the assessment found.

Its smaller surface area makes it more difficult for Russian systems to detect and intercept, the documents said. Ukraine first received the aerial weapons, which has not been previously disclosed by the Pentagon, in November 2023.

The GBU-39 was also adapted for land use in HIMARS systems, a development that Pentagon officials said would increase the range of rocket artillery. But the modified weapons, known as Ground-Launched Small Diameter bombs, or GLSDB, proved ineffective compared to those launched from airplanes, Ukrainian officials said. The ground versions were tested in Ukraine, one official said, and the Americans are working on adjustments before providing them anew.

William LaPlante, the Pentagon’s acquisition chief, said last month that an adapted weapon “didn’t work for multiple reasons,” including jamming and other tactical and logistical issues. LaPlante did not disclose which weapon he was referring to, but other experts said that he was describing the GLSDB.

“When you send something to people in the fight of their lives,” LaPlante said, “they’ll try it three times and then they just throw it aside.”

Senior Ukrainian military officials said Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missiles, provided by Britain, are less susceptible to Russian jamming because they do not rely solely on GPS but two other navigation systems, including an internal map that matches the terrain of its intended flight path. Russian air defenses nonetheless have had some success intercepting them.

The Ukrainians have also had success so far with U.S.-provided Army Tactical Missile System long-range missiles, which have a range of up to 190 miles, but they, too, can be targeted by Russian air defenses.

The Ukrainian officials said they expect that weapons effective on the battlefield now will similarly slump within a year.

“The Russians will learn how to fight it,” the second Ukrainian official said. “That’s how the arms race works.”

Horton reported from Washington.

Related

EU denies picking on US tech giants, says US also…

BRUSSELS (Reuters) - Europe's new tech rule aims to keep digital markets

H-1B Visa 2025: How and why US policy shift may…

Recent changes in US H-1B visa policies have sparked significant concern within the Indian IT professional community hoping to work in America. However, the a

Alibaba Group (BABA) Stock: Chinese Tech Giants Gain $439 Billion…

Chinese tech stocks have gained over 40% this year, adding $439 billion in valueChina’s “7 titans” are outperforming the US “Magnificent Seven” tech s

The Global Spread of Protectionist Policies That Squeeze American Tech…

An increasing number of countries in recent years have begun targeting America’s leading technology firms with policies touted as measures to promote fair com