The quaint English town where the US’ future was planned

Alamy

AlamyThe politely radical English town where one of America’s Founding Fathers, and the world’s first international revolutionaries, sparked a spirit of rebellion that continues to this very day.

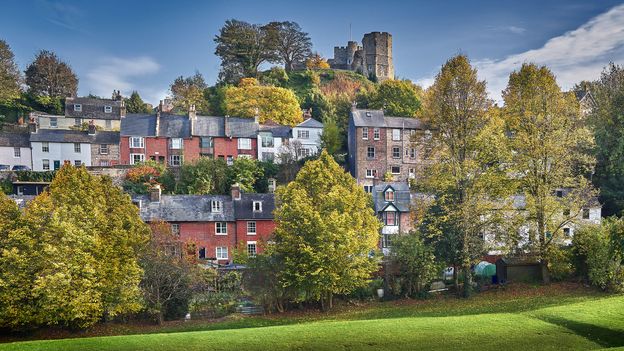

The town of Lewes, with its picturesque cottages and bustling high street full of antiquarian bookshops and artisanal bakeries, might seem the very model of traditional English respectability. Named the “prettiest place in the UK” by The Telegraph (a trusted arbiter of British middle-class tastes), sedate tea shops and art galleries line the medieval alleyways where smartly dressed locals greet each other courteously. Even the local flea market, housed in a former Methodist chapel, is an upstanding example of grand Victorian architecture.

Yet beneath this veneer of conservative conformity lies a history of radicalism that runs to the core of this quaint Sussex town.

Each year on 5 November, Lewes turns into a blazing frenzy of raucous anti-establishmentarianism. Its cute coffee shops and organic grocery stores lie abandoned as grotesque effigies (or “tableaux”) of public figures – ranging from British prime ministers and business leaders to the Pope and, more recently, Joe Biden and Donald Trump — are set on fire and paraded through the streets.

Lewes Bonfire Night Celebrations, the biggest and oldest in Britain (dating to 1795), exemplify the spirit of rebellion in this town where Thomas Paine, the English-born American Founding Father, political philosopher and one of the world’s first international revolutionaries, lived 250 years ago

Paine, whose writings influenced both the American and French Revolutions and helped inspire the US Declaration of Independence, lived in Bull House on Lewes’ High Street from 1768 to 1774. While working there as an excise officer, collecting taxes on behalf of King George III, Paine was a frequent speaker at a political debating society, The White Hart Evening Club. Its meetings were held at 16th-Century inn The White Hart, also on Lewes High Street, which recently reopened after a major refurbishment as a luxury hotel complete with restaurant and bars, yet retains many of the original features from Paine’s time, including his initials carved into one of the fireplaces.

Nick Smith Photography

Nick Smith PhotographyThe debating society later changed its name to the Headstrong Club but, now under new management, The White Hart has once again become a centre of life in Lewes. It’s also a place of pilgrimage for Americans fascinated to see where many of the ideas that would eventually lead to the birth of their nation were first formulated; as well as for the politely radical citizens of Lewes who celebrate Paine’s memory and the enlightenment principles he espoused.

I meet in the hotel’s lounge with Richard Powell, a retired diplomat who is the current chairman of the new Headstrong Club, relaunched in 1987 on the 250th anniversary of Paine’s birth. Over a bottle of Tom Paine ale – brewed locally by Harvey’s who were established in 1790 and own several pubs in the town, including The Rights of Man across the road, named after one of Paine’s seminal works – Powell tells me how the American Founding Father’s spirit is very much alive in Lewes.

“Any ‘citizen of the world’ is welcome,” he says, quoting one of Paine’s famous phrases, “at our monthly meetings [now held at the Elephant & Castle pub within walking distance of The White Hart]. They can just pay £5 on the door. We’re also happy to be approached by people wanting to propose a subject to speak about, just like Tom [Paine] used to. We get viewpoints right across the spectrum, and some of them do occasionally cause pain – no pun intended – such as the time we had a discussion on gender identity and the police had to be brought in to deal with threats being made to some opinion holders.”

Might the US’s new president-elect be a future subject for debate, I ask him. “Not while I’m in charge,” Powell laughs. “We tend more towards things like the politics of climate change, or the role of church and state – a topic that Paine himself felt and wrote strongly about.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA statue of Paine stands proudly outside the town’s library, whilst his tradition of bold political discourse is also honoured at the annual Lewes Speakers Festival. The January 2025 event will feature Penny Mordaunt, the former UK Secretary of State for Defence, talking about how the country’s deep divisions can be overcome by political reform. A subject that Paine – who once said, “We have it in our power to begin the world over again” (quoted in speeches by both Ronald Regan in 1980 and Barack Obama in 2009) – would have no doubt approved.

After being fired from his job for attacking its pay and conditions in his first published pamphlet, “The Case of the Officers of Excise”, Paine left Lewes for Philadelphia in 1774, intending to make a new life in the American Colonies (on the advice of Benjamin Franklin whom he had met in London). It was here that he used the political skills he had honed in Lewes to write “Common Sense”. This 50-page pamphlet, the most widely read during the American Revolution, sold more than half a million copies and paved the way for the Declaration of Independence, which Paine is believed to have helped draft, by advocating for a republican government free from British control.

Bull House, where he lived, is now in the hands of the Sussex Archaeological Society; established in 1846, it is the oldest of its kind in Britain. According to the Society’s museums officer, Emma O’Connor, Lewes is a magnet for visiting history lovers as well as for residents moving here from the capital (known as DFLs: “down-from-Londoners”), many of whom commute to arts and media jobs in London, just more than an hour away.

“A lot of Thomas Paine’s Lewes would still be familiar to him today,” she said. “Lewes is a historic town and all the best bits are still there. And for anybody that has a mind to, there’s a lot going on that’s of interest and lots of avenues for self-enlightenment, whatever your interests may be. We’ve Glyndebourne [opera house] on the doorstep, as well as Brighton a few miles down the road. And you can’t fail to notice that bang in the middle of Lewes High Street, there’s a stonking great castle!”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOriginally begun just after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 (the site of which lies less than 25 miles to the east of Lewes), the Norman castle took 300 years to complete. It is open to the public and now adjoins Lewes Museum, which covers all periods of the town’s history, including Paine and the annual bonfire celebrations.

More recently, one of the most famous of all people connected with Lewes – and one that perfectly embodies the town’s spirit of “respectable and reserved on the outside, radical and revolutionary on the inside” – is the writer Virginia Woolf. Part of the Bloomsbury group, a coterie of avant-garde artists, writers and intellectuals whose uninhibited, polyamorous lifestyles predated the 1960s’ sexual revolution by decades, Woolf took rooms in 1910 at The Pelham Arms on Lewes High Street. She later owned the Round House in Pipe’s Passage, a building she described in a letter to the painter Dora Carrington, as “the butt end of an old windmill”. Her final, more aesthetically pleasing home – and inspiration for her short story The Orchard – Monks House in neighbouring Rodmell, was purchased at an auction in The White Hart.

Vanessa’s grandson (and Virginia’s Woolf’s great-nephew), Julian Bell, is himself an artist and fellow Lewesian. He believes “the Lewes area has always had a community on the radical, liberal side, including some of my ancestors who were, I suppose, the original DFLs”.

Bell’s mural of Thomas Paine, painted in 1994, is on display in the town’s Market Passage. And, for this year’s Lewes Bonfire Celebrations, he helped create a tableau of the Houses of Parliament which were then blown up as part of the town’s anarchic festivities. “We were fulfilling Guy Fawkes’ intentions to destroy the seat of parliamentary democracy,” Bell tells me, jokingly.

Russell Higham

Russell HighamPaine and his respectfully rebellious friends at The White Hart preferred a less direct form of action to Guy Fawkes: the power of the printing press. Before the days of electronic communications, printed pamphlets were the social media posts of their day; used by activists and thinkers, such as Paine, to disseminate ideas and rally national or even international support for change and justice. A press similar to the one that Paine used to publish his pamphlets is on display across the road from Bull House at The Tom Paine Printing Press and Gallery.

“The world is my country, all mankind are my brethren” is another of the favourite sayings of the political philosopher, whose writings inspired and helped shape revolutions in both America and Europe. However far and wide this pioneering revolutionary and his rebellious ideas travelled, though, there will forever be a part of him that remains in Lewes. For those looking to change the world themselves – or merely enjoy a quiet pint by a cosy fireplace – The White Hart in Lewes is not a bad place to start.

Related

Canada says too little, too late as Trump flip-flops on…

Nadine Yousif and Ali Abbas AhmadiBBC News, TorontoWatch: Canadian liquor store clears out US alcohol in response to tariffsNot long after the US imposed their

Vietnam, Thailand, and Philippines Among Top Asian Destinations Most-Searched by…

Home » Philippines Travel News » Vietnam, Thailand, and Philippines Among Top Asian Destinations Most-Searched by American Travelers, Driven by Surge in Viet

Trump tariffs tarnish ties: Americans anxious about travel to Canada…

Will Trump's tariffs on Canadian goods entering the U.S. affect tourism at home, tarnishing ties Canadians and Americans have shared for decades? It's a fair qu

Looming Trump travel ban strikes fear in Afghans who worked…

Expectations that President Donald Trump will soon bar Afghans and Pakistanis from entering the United States has set off panic among Afghans who were promised