True State of US Sports Betting: Negative Effects Overblown

NEW ORLEANS — Visitors flying into Louis Armstrong International Airport for this week’s Super Bowl will see multiple sportsbook advertisements before they reach baggage claim. Along the roughly 15-mile drive to New Orleans’ Central Business District, a traveler will pass by at least a half-dozen billboards for sportsbooks and casinos.

Along Canal Street, the city’s flamboyant thoroughfare that greets revelers to the French Quarter, there is a multi-story advertisement plastered along a building for FanDuel’s “Kick of Destiny” a coming Super Bowl TV ad featuring New Orleans natives and NFL champion quarterbacks Peyton and Eli Manning. Caesars New Orleans casino stands a few blocks south, fresh off a $435-million renovation featuring its glistening 5,700-square-foot sportsbook.

Super Bowl LIX, which is set to draw more wagers at legal sportsbooks than any event in American history, will be played a mile from the casino at the Caesars Superdome.

Key Points:

- Sports betting participation has increased each of the past few years, especially among younger male bettors

- More than 50% of Americans who wager are still not betting with legal sportsbooks

- 75% of bettors have deposited less than $500 total over the past five years

- Of “frequent” bettors (gambling at least once a month), roughly half are betting less than 1% of their annual salary

- Bettors may be shifting money from savings to gambling, but more research is needed

- Additional studies show no increase in suicide or other significant macro-level mental health issues in legalized states

- Addressing the small minority of problem bettors on both ends of the financial spectrum should be the focus, not sweeping regulations

I – Sports Betting Big Picture

The NFL’s upcoming Super Bowl will be the latest financial highwater mark for regulated sports betting in America; the most gambled-upon single-game competition in the most wagered-on league.

A record 38 states (plus Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico) will accept legal wagers on this year’s game. More than 28.7 million adults were projected to have placed a bet with a licensed bookmaker on Super Bowl LVIII in Las Vegas, per the American Gaming Association (AGA), a number that is set to be topped in 2025 – even away from the nation’s gambling epicenter.

After decades of opposing legal sports betting, the NFL’s marquee event will be played for the third consecutive year in a state that allows attendees to place bets on their smartphones from their seats.

The increased wagering on the Super Bowl comes as sports betting participation – and revenues – have increased each year since the Supreme Court struck down the federal wagering ban in May 2018, allowing individual states to legalize single-game sports wagering within their borders and create their own regulations, tax rates, and licensing requirements.

As the legalized gambling jurisdiction total increases, so too does bettor participation:

-

An annual Seton Hall University poll conducted in conjunction with each recent Super Bowl has shown the number of Americans that have placed at least one bet on a sporting event has increased from 28% of the adult population in 2022 up to 37% in 2024.

-

Since Nevada lost its position as the only state to accept legal single-game sports wagers, licensed sportsbooks have grown their total handle (bets placed) from less than $7 billion for calendar year 2018 up to more than $121 billion in 2023. Hold percentages (percent the sportsbooks have won) and bookmaker revenue have increased each year.

-

Legalization, and marketing, have also ignited a corresponding boom in sports betting app downloads from six million in 2019 to 33 million in 2024, per a SensorTower report.

-

U.S. sportsbooks are expected to have generated more than $14 billion in reported gross revenue and roughly $150 billion in handle for calendar year 2024. This does not include totals from Florida (which doesn’t disclose these figures publicly), California or Texas (which don’t permit sports betting).

One can extrapolate that if the other half of the U.S. population had access to legal sports betting, the annual revenue figure from regulated books would have been closer to $28 billion and the total handle closer to $300 billion.

Legal books’ unsubtle approach leads to impassioned responses

The regulated sportsbook ads, which appear most prominently at the start and end of each football season, may have rubbed elected officials and their constituents the wrong way. Still, they have achieved their purpose.

A 2024 St. Bonaventure University/Siena College poll found that 75% of respondents had seen a sportsbook ad. For those attending this year’s Super Bowl – or watching it – that figure will be nearly 100%.

Though FanDuel and DraftKings now have generated upwards of 70% of all U.S. gross sports betting revenue (a de facto duopoly that has also drawn attention from policymakers), promotional spending has made it difficult for either company to consistently turn profitable quarters.

That is largely because the companies have invested hundreds of millions in digital and social media promotions – as well as advertising on billboards, TV programs, radio shows, podcasts, and nearly every other medium imaginable.

Hundreds of millions more were spent on “free” bets, or sportsbook-specific “cash” losing bettors could retain if their initial wager lost. More than seven out of 10 respondents in the St. Bonaventure survey said they started betting with or because of the promotions, which in the first few years after the federal wagering ban was repealed could be worth up to $3,000 in “free” bets for first-time depositors.

Both the practice of (what had been called) “risk free” bets as well as the advertising practices have drawn scrutiny from state gambling regulators, Congress and nearly all 50 state legislatures and newsrooms across the country.

I can picture the Massachusetts Gaming Commission meeting already https://t.co/bUKtugSnRu

— Geoff Zochodne (@GeoffZochodne) March 24, 2024

A sweeping bicameral 2024 bill would mandate federal oversight of the current state-by-state sports betting markets and, perhaps most notably, drastically restrict advertising. The powerful Senate Judiciary Committee, in one of its last acts following the 2024 elections, discussed the bill as part of a larger hearing on sports betting in America.

These lawmakers’ actions have been accompanied by a nearly unprecedented fusillade of excoriating headlines from a range of the nation’s most prominent publications.

“I Got Divorced Because of Sports Gambling” reads a January 2025 feature by New York that detailed the troubles three women had with their gambling-addicted partners. “I Really Can’t Stop. The Descent of a Modern Sports Fan” blared The New York Times’ sports-focused vertical The Athletic in an October 2024 piece that detailed a gambler who lost most of a year’s salary betting on sports.

In September, The Atlantic called for the federal wagering ban to return in “Legalizing Sports Betting was a Huge Mistake.” The Washington Post editorial board expressed similar dismay in a series of opinions throughout 2024, capped off by its Dec. 29 piece “Legalizing sports gambling was a terrible bet,” which called for sweeping federal regulation.

In the weeks leading up to and after the Post editorial, Bloomberg didn’t mince words in “Sports Betting Apps Are Even More Toxic Than You Thought,” Esquire waxed on sports betting’s impact on Black Americans in “The Problem with Legal Gambling That Everyone Seems to Be Ignoring,” and The New Republic declared “America’s Online Sports Betting Crisis is Already Here.”

These were accompanied by scathing opinion pieces in the Arizona Republic, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Missouri Independent, and outlets from across the country.

In Minnesota, one of the handful of remaining U.S. jurisdictions with in-person casino gambling but no legal sportsbooks, several of these opposition pieces were cited in a legislative hearing exposing the dangers of gambling. Lawmakers also heard testimony from a study that found instances of domestic violence increased in states with legal sports betting when home NFL favorites lost.

Academic analyses as the basis for criticisms

In their criticisms, many legal sports betting opponents cited from a trio of lengthy academic studies released in 2024 that looked to explain the impacts of the sports betting phenomenon. The findings were largely negative.

In “Online Gambling Policy Effects on Tax Revenue and Responsible Gambling,” a team led by Southern Methodist University assistant professor Wayne Taylor finds that online sports betting legalization increases irresponsible gambling and calls to gambling hotlines, especially when online casino gambling such as digital slots and table games was also legalized. The study observed more than 700,000 gamblers across 14 states with competitive legal online sports betting markets over nearly five years.

Most critically, the study did not find a rise in suicides brought by gambling legalization, the more pressing and damaging potential side effect of gambling. This further refutes common misnomers cited by legislators and the public of “sky-high” suicide rates associated with gambling as justification to prevent it.

A team led by UCLA associate professor Brett Hollenbeck found a host of negative financial metrics in states that legalized online sports betting.

“The Financial Consequences of Legalized Gambling” determined through a study of seven million credit card users that average credit scores decreased by 0.3% within four years after states legalized sports betting. This led to more debt sent to collections, more debt consolidation loans, and auto loan delinquencies in states that legalized online sports betting compared to those that didn’t.

The paper postulates credit agencies are lowering their limits in legal sports betting states to reduce their exposure to customers with higher financial risk.

“If no action is taken, it is highly likely that the large increase in sports betting will lead to a long-term increase in financial stress on many consumers and policymakers and financial regulators should be prepared for this,” the study found.

Despite these observed financial declines, the study did not find this led to a significant increase in bankruptcies, a critique noted in other academic research papers. The Hollenbeck study also acknowledged that these financial health declines were correlations with legal sports betting, not necessarily the result of legalization.

Northwestern University assistant professor Scott Baker found sports betting legalization hurts savings, especially among lower-income households. In “Gambling Away Stability: Sports Betting’s Impact on Vulnerable Households,” Baker’s paper used observations from more than 230,000 American households to determine sports bettors in regulated markets were funding gambling through money previously reserved for long-term savings accounts, heightening financial instability.

Baker’s group found this led to a 14% decline in net investments and a direct loss of $1 in investments for each $1 deposited into a sportsbook.

The study found that sports betting legalization did not diminish participation in lotteries or other gambling forms, and led to only a negligible deposit change in cryptocurrencies or so-called “gamified” brokerages such as Robinhood. It also showed that bettors in legal sports betting states increased their spending on complementary goods including cable, restaurant visits, and “other entertainment” that it projects complements the sports betting experience.

Per Baker, the results show that sports betting doesn’t increase household spending but shifts it away from savings to entertainment. The paper does not analyze the intangible emotional utility sports bettors may enjoy, even at the expense of traditional long-term savings accounts.

These widespread financial concerns seem not to consider, or even run against, the demographic and financial makeup of most individual bettors and their widely disparate participation levels – data points that these studies published in their papers.

A portion of Americans see adverse consequences from gambling, costs that could logically be exacerbated by increased access. But the data shows this is a small subset within a minority – and perhaps not indicative of these macro-level observations.

II – The “Average” Sports Bettor

The captious Atlantic piece uses the Seton Hall survey to declare that more than one-third of Americans gamble on sports. The reality of who and how much they are gambling is far more nuanced.

The studies reiterate prior research (and anecdotal observations) that U.S. sports bettors are predominantly male (75% compared to 25% for females) and younger than the national average, an overlapping demographic group less averse to risky behaviors such as gambling.

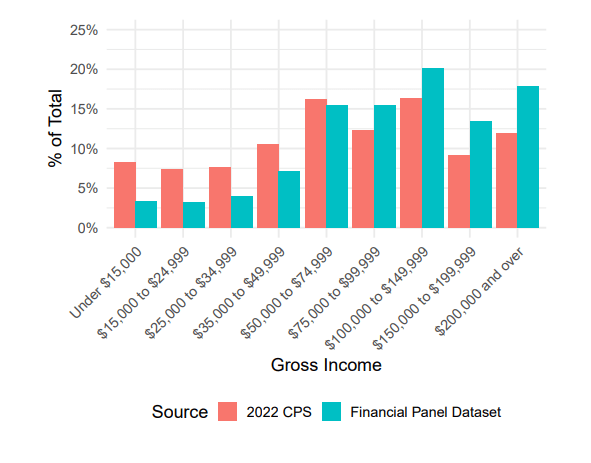

The data in Taylor’s research reaffirms sports bettors have higher-than-average incomes. The “average” sports bettor’s annual household 2023 income ($130,000) is roughly 25% higher than the national mean ($106,000). Nearly 30% of bettors had annual household incomes above $150,000.

The Taylor study shows that most customers who deposited into a major U.S. online sportsbook made two or fewer deposits in the nearly five-year survey period. Most potential gamblers did not gamble at all within any particular month.

For the vast majority of those who placed bets, sports betting spend represents a minuscule percentage of their overall income.

The Taylor group’s nearly five-year observation period found the average sports bettor made 18 mobile sportsbook deposits. This average is skewed by the small percentage of bettors who made 87 or more deposits; more than 75% of those surveyed made seven or fewer deposits during the survey’s duration.

The study found the “average” bettor made $1,375 worth of deposits, but three-fourths of bettors deposited $500 or less over 4.75 years. This figure is even more heavily skewed by a small number of large-money depositors; the “median” gambler deposited only 10% as much as the “average” gambler. That means half of those studied deposited less than $135.

Nearly three-fifths of bettors surveyed in Taylor’s data spent less than 1% of their annual salary in the months that they gambled. Only 3.2% spent more than 15% of their income, underscoring an industry where money spent is heavily skewed by a small percentage of participants.

Taylor’s study of spending and loss figures are also potentially inflated. Twelve of the 14 observed states only allowed online sports betting, but Connecticut and Michigan permit real money iCasinos. The study did not differentiate between digital slot or table game spend and online sports betting spend.

The Baker survey of roughly 230,000 households over more than five years found legalization started a series of about $25 average deposits each quarter (roughly $100 a year) across the entire population, not just bettors. Among those who place bets, that quarterly deposit figure is $180 per quarter, or roughly 2.5 times the $72 average quarterly spend that Taylor’s survey found. The average total deposit was about $2,300 over 21 months in that survey period, or about a 40% increase compared to the 19 months recorded in the Taylor report.

This equates to Baker’s findings that betting deposits increase over time. Baker’s study also found that these figures level out after a certain period.

Both Baker and Taylor found that most betting comes from a small set of high-intensity bettors.

Baker’s study found the top third of bettors based on total deposit value spent nearly $300 per quarter, or 1.75% of their income. The bottom third averaged only $1.39 per quarter, meaning they spent less than $30 at legal sportsbooks over more than five years.

Roughly half of bettors in Baker’s survey are still betting in the rolling 12-month period after placing their initial deposit. Still, only 38% of bettors will make more than 10 deposits in the initial three-year period after their state legalizes mobile sports betting, Baker found.

These studies align with recent surveys that show sports betting sees a disproportionate percentage of its action from a small percentage of frequent bettors – and is largely avoided by most of the public.

Surveys reaffirm study data

The St. Bonaventure survey found that only 5% of respondents bet on sports every day. The study found 33% bet at most once a month and that 62% never bet. Those figures align with the Seton Hall poll that found 37% of Americans were considered “bettors” because they had placed a lifetime bet.

Nearly three-fifths of these account holders never made a second deposit or deposited “only once in a while,” mirroring the academic study’s findings.

Not surprisingly, male respondents under the age of 49 were the most likely to bet frequently.

Less than one-fourth of respondents in the St. Bonaventure poll said they had ever gambled more than $500 in one day with an online sportsbook.

Among all surveyed bettors, 83% said they like to place small bets with big payouts. This also suggests a growing trend reported in the major sportsbooks’ financials that bettors are placing occasional, improbable, small-risk/big-return bets.

This indicates for many sports bettors the enjoyment of placing a sports bet is similar to purchasing a lottery ticket.

The annual Seton Hall survey showed that while more Americans are placing at least one bet overall, many are still not betting more than a few times a year. Both the 2024 and 2023 editions show that 50% of American adults who had at any point bet on sports had not placed a wager in the past six months.

A November 2024 YouGov poll echoed the academic papers’ financial discoveries by finding that roughly two-thirds of self-reported sports bettors wager less than $100 a month. Only about 10% gambled more than $500 monthly.

These figures come on the heels of a 2023 piece – “Data from New Jersey is a warning sign for young sports bettors” by the Rutgers University Center for Gambling Studies Department – that found about 5% of New Jersey sports bettors placed nearly half of all bets. That accounted for roughly 70% of the money wagered.

How many sports bettors are there?

The St. Bonaventure poll found that nearly one in five Americans above age 21 (about 50 million people) has opened an account with a legal sportsbook. That was compared to the Seton Hall study that showed 37% of respondents had placed a bet, but not necessarily with a regulated sportsbook account; it also could include friendly wagers with friends or an unlicensed operator.

Both university polls (and common sense) indicate that there is tremendous overlap between sports bettors and the hard-to-define term sports “fans.” One would assume that nearly all bettors, of nearly any frequency, would define themselves as a “fan.”

Taking the roughly 50 million-person average viewership of the NFL’s conference championship games, perennially the second and third-most viewed American sports events after the Super Bowl, it can be inferred that a significant portion of sports “fans” have opened a sportsbook account but have not placed a second deposit.

Those betting regularly enough to accurately be considered “sports bettors” are, naturally, smaller than those that have registered.

Data from GeoComply, a geolocation technology partner with all major regulated sportsbooks, tallied all login attempts in each legal sports betting jurisdiction and divided that by its population. The data showed less than 10% of Americans are betting on an average NFL Sunday, among the most popular dates on the sports betting calendar.

During NFL Week 6 games in October, Washington, D.C. had the most active sports betting accounts per capita at 8.2%. Colorado, with the eighth-highest percentage, saw only 5.6% of its population log into a sportsbook account. This login attempt data didn’t account for bettors with multiple accounts, meaning the actual percentage is undoubtedly smaller.

FanDuel and DraftKings both report between three-to-four million monthly active users in public financial filings. They each have over one-third of the national U.S. handle by market share apiece and were cited in multiple of the aforementioned studies as the most popular sportsbooks.

Legal sports betting jurisdictions create their own regulatory structures, so there are states where sports betting is legal but DraftKings and/or FanDuel is not available. One can assume there is somewhere around 20%-to-30% of the monthly active betting population using legal sportsbooks but not the two market leaders.

The St. Bonaventure poll found that 56% of respondents use exactly two or three books, with only 7% using four or more. Not accounting for the overlap of customers with multiple books, it’s safe to project from the sportsbooks’ publicly released consumer data that there are around 10 million Americans placing bets at least once a month or about 5% of the adult population of roughly 250 million.

Though major events such as the Super Bowl will lead to 20 million or more individuals placing a bet with regulated books, most are content to wager sporadically.

Gambling is clinically proven to be addictive and must be evaluated separately from other disposable entertainment options such as streaming services or concert tickets. Still, this means even among the minority of Americans who have ever placed a legal bet, most will spend less money each month gambling on sports than they would on a Netflix subscription.

Are there winning bettors?

The Taylor survey found, as expected, that both big and small spenders lost money; less than 5% of surveyed bettors withdrew more than they spent. However, the scales of the losses were comparatively minor for the bulk of bettors.

The “average” bettor lost $633 over the nearly five-year study period, during which time they earned more than $600,000 in income. Less than 25% of bettors surveyed lost more than $365, with losses again heavily concentrated to a small percentage of bettors.

SMU monitored 700,000 online sports bettors. Less than 5% withdrew any profit

The rest were were losers 3% of the losers lost so much they made up for 50% of the revenue pic.twitter.com/WDcHYOKrSk

— Saagar Enjeti (@esaagar) December 5, 2024

Only 43 of the more than 700,000 people surveyed deposited more than $500,000 over the roughly 4.75 years in the surveyed period, with 33 of them losing money. Winning, too, is skewed toward a small percentage; the roughly 5% of bettors that withdrew more money than they deposited collectively earned more than $100 million.

As the studies, the Washington Post, and many “professional” bettors (on social media) have noted, many major sportsbooks have limited the size of bets placed by winning bettors or banned them outright. While this is no doubt a major concern for the minuscule percentage of winning bettors and part of a larger discussion of the industry, it is a comparatively minor concern in the overall structure of regulated sports betting that has been attacked by elected officials and much of the mainstream media.

These studies don’t differentiate between millionaires who can gamble (and lose) significant amounts without corresponding financial households and lower-income earners who can’t. But the academic research, despite tangential external determinant impacts that stakeholders agree should be further understood and studied, shows that for around 90% of bettors, gambling on sports is a relatively minor financial undertaking.

Additional research refutes negative studies

Perhaps because high-frequency betting is confined to such a small percentage of the population, the widespread potential macro-level financial impacts are not showing up in Americans’ mental health, a contrasting 2024 academic study finds.

Along with Baker’s survey that shows no statistically significant changes in suicide rate brought on by legal gambling, a 2024 paper led by Wofford College’s Tim Bersak finds that there is no tangible change in a wide range of mental health factors ushered in through sports betting legalization.

In “Impacts of Access to Legal Mobile Sports Betting on Self-Reported Mental Health,” Bersak and his co-authors analyzed nearly two million people surveyed in the Household Pulse Survey (HPS). The program was created shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 to evaluate real-time opinions on urgent issues.

Respondents in the evaluated HPS were checked to see self-reported changes in anxiety, level of worry, loss of interest, employment and earnings, as well as “feeling down or depressed.” Bersak’s team analyzed respondents in the states that had legal statewide mobile sports betting when the survey began against the additional states that had legalized mobile wagering in fall 2024. This was cross-referenced against states that had no legal wagering at any time in any period.

The study found no noticeable changes in any of the studied negative emotions.

“In spite of this popular narrative, there is relatively little evidence establishing the causal impacts of access to legal mobile sports betting on mental health or financial distress in the United States,” the study found.

Since each state launched legal sports betting individually between 2018 and 2024, Bersak’s research evaluated how states such as New Jersey and Pennsylvania that started accepting wagers in 2018 saw their mental health reporting change and weighed that finding against more recent adopters. The research found no change as sports betting grew.

“Once again, we do not find any evidence of impacts that are increasing over time following the establishment of legal online sports betting within a state.”

Bersak’s study also challenged the findings in Hollenbeck’s research that determined sports betting had led to a rash of negative financial consequences.

The Hollenbeck study found that bankruptcies had not increased, though other financial health metrics such as credit scores had decreased. Bersak wrote that since bankruptcy remains an unusual outcome, the estimated impacts could come from a tail of distribution among a small percentage of those surveyed, disproportionally altering the population-wide average.

That would reflect the broader study and survey data that showed a massive portion of sports betting dollars wagered was confined to a tiny portion of the population.

What explains the difference?

Newly released academic studies are “working” papers subject to further review and peer scrutiny. They are observers’ best attempts at understanding a topic but are not infallible.

The paper cited in the Minnesota sports betting hearings that projected home NFL favorite losses increased incidents of domestic violence used geographic county-level data, not more logical political boundary information to determine a “home” team. Residents in Kalamazoo County, Michigan – deemed a Green Bay Packers “home” county – are far more likely to support the in-state Detroit Lions. It also did not consider the disparate levels of fan attachment (there are far more fans of the Pittsburgh Steelers than the Jacksonville Jaguars).

More significantly, none of the academic studies appeared to account for the scope – and prevalence – of unlicensed bookmakers despite the expansion of the regulated industry. The ads for legal sportsbooks undoubtedly encouraged more betting participation, even if it wasn’t with its sponsor.

It’s possible the bettors getting into the most dire financial situations are not just wagering with the legal books, but also through or exclusively with illegal sites.

A 2024 survey by the UMass School of Public Health and Health Sciences found that participation in Massachusetts illegal sports betting had not declined between 2022 and 2023, the year when legal mobile sportsbooks launched in the commonwealth. This indicates previous bettors are sticking with the black market even when new legal options come online.

They could also be potentially seeing ads for legal books and confusing them with unregulated bookmakers.

David Rebuck, New Jersey’s former top gaming regulator, railed during the 2024 congressional hearing against offshore sites promoting themselves on search engines in a state with the most per capita legal online betting offerings. As marketing and societal changes have made all sports betting more socially palatable and accessible, the thousands of offshore sites are also taking advantage of a growing potential customer base.

Today, every state in this nation has illegal sports betting readily available to its citizens, Rebuck says. States already adopting best practices such as partnering with academic institutions for RG research. Industry also engaged in research.

— Geoff Zochodne (@GeoffZochodne) December 17, 2024

Though in-person underground “bookies” have become less common as technology becomes more accessible, through convenience or confusion, it’s clear a massive number of Americans are betting with offshore sites, as prior AGA projections indicate.

A 2022 letter from the AGA to then-Attorney General Merrick Garland said the majority of bettors (52%) were still using illegal bookmakers despite the growth of the legal market.

The letter noted that internet searches for offshore sportsbooks increased 38% in the year prior, pacing ahead of the search growth for legal books.

These sites oftentimes promote bets with credit cards or cash advances that regulated books can’t or will not offer. These sites don’t advertise on NFL broadcasts but still promote on social media, podcasts and many other outlets.

In the absence of federal action to stop these sites that originate overseas, individual states have more aggressively pushed offshore sites to cease operations. Not coincidently, most of these states leading the charge offer legal sportsbooks.

Though the regulated market has ample faults, it is one way – perhaps the best way – to funnel resources and customers to problem gamblers. Black market betting, as the regulated market will be quick to point out, generates no taxes and offers no player protections.

Problems arise when bettors gamble beyond their means or have no tools to stop them; the black market offers no assistance in either category.

Part I – Negative Effects of Gambling Legalization Overblown

Part II – The American Bettor (Monday 12 p.m.)

Part III – Perception (Tuesday)

Part IV – Regulation (Wednesday)

Part V – Integrity (Thursday)

Part VI – Wish List (Friday)

Pages related to this topic

Related

Sports Betting Giant Flutter Forecasts Strong U.S. Growth To Drive…

Flutter CEO Peter Jackson.Courtesy of Flutter Entertainment Flutter Entertainment, the world’s largest online gambling company, said that it’s expecting str

BetBlocker Enters US Responsible Gambling Market

The charity, originally from the UK, launched a US unit, BetBlocker US, as part of its North American entry. The organiz

Viewers react to ’embarrassing’ JD Vance comment toward Zelenskyy as…

Social media users watching clips of the heated meeting between President Donald Trump, Vice President JD Vance and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy have called a

Ukraine latest: Zelensky urges Trump to stand ‘more firmly on…

We have Zelensky's statement in full Below, we have Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky’s statement in full after touching down in the UK following a fiery