Last week, two series about sensationalized true-crime cases, produced by Hollywood mogul Ryan Murphy, premiered: American Sports Story: Aaron Hernandez on FX and Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story on Netflix. While the two shows—the former about the rise and fall of an NFL star convicted for murder and the latter about the killings of José and Kitty Menendez by their sons—don’t have many similarities, they do share several hallmarks. Murphy is an executive producer on both series, each a spinoff of his true-crime franchises, and there’s a significant focus on the titular subjects’ sexualities—particularly pertaining to homosexuality and childhood abuse.

In Monsters (and real life) Lyle and Erik’s defense hinged on their claims that they killed their parents as an act of self-defense, after years of alleged sexual abuse. And before Hernandez was pushed over the edge by the hyper-masculine football industrial complex, he had closeted homosexual experiences and was allegedly molested in his youth—though none of those details were brought to light until years after he stood trial. While at first it seems Murphy intends to paint a full picture of his subjects in these shows (and others like 2018’s American Crime Story: The Assassination of Gianni Versace) by looking into their private lives, it quickly veers into salaciousness territory by including speculative information. But Monsters and American Sports Story could have gone (and arguably would’ve been better shows) without dissecting the sexuality of each of its subjects. In many ways, it feels unnecessary and repugnant, as these shows only further scandalize sensitive and true stories that have already been tabloid fodder for years.

Throughout Monsters, Erik (Cooper Koch) and Lyle Menendez’s (Nicholas Chavez) closeness is depicted in scenes with homoerotic context.

(Image credit: Courtesy of Netflix)

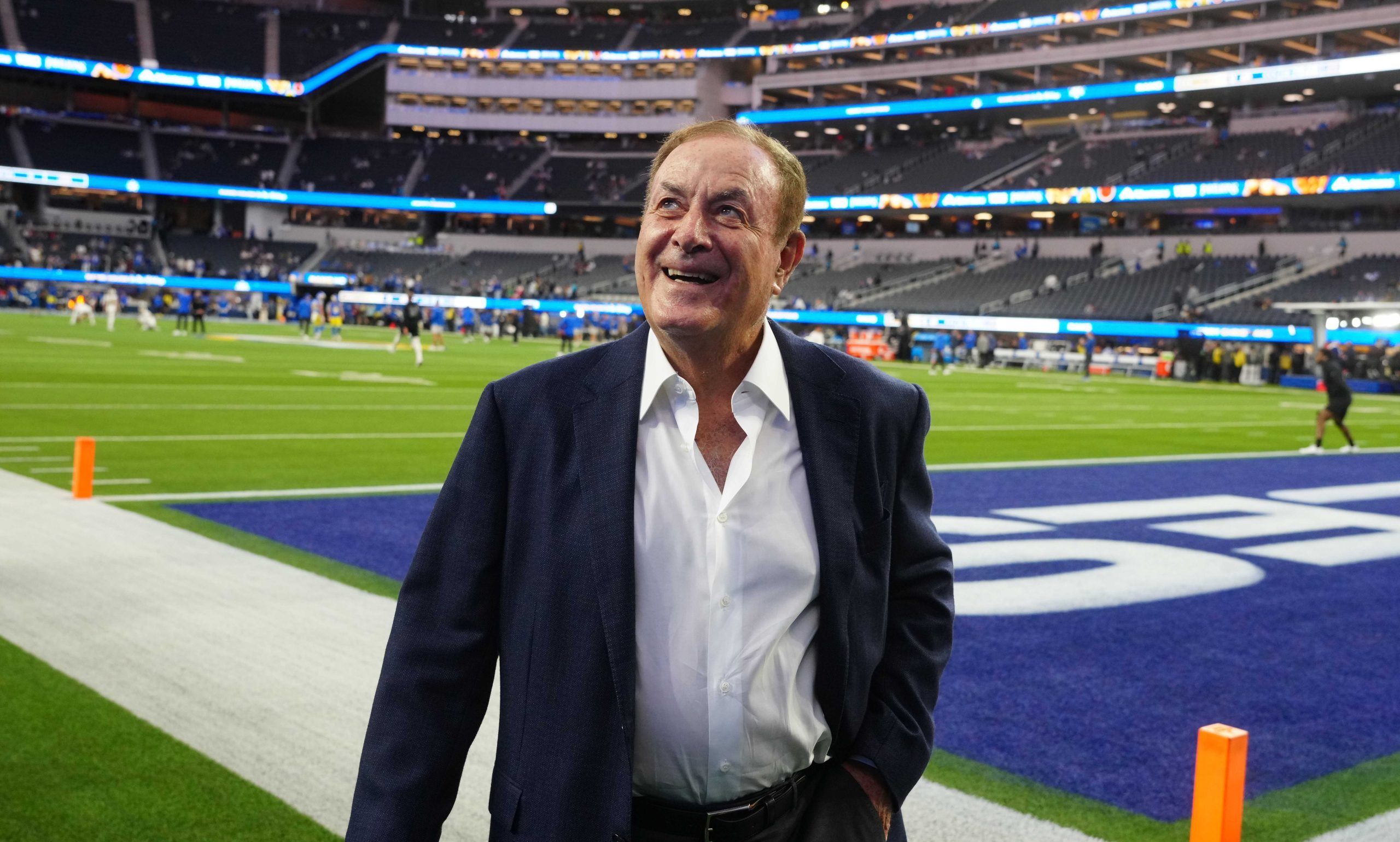

Though it premiered to much less fanfare than Monsters, the first season of American Sports Story has all the traits that a Murphy production (American Horror and Crime Story, Ratched, Hollywood, Nip/Tuck) is known for: character studies, snappy dialogue, immersive period-appropriate styling, and intense sexual content. Co-written by series creator Stuart Zicherman, Sports Story distinguishes itself from the rest of the showrunner’s true-crime anthology series with its exploration of the NCAA and NFL and how football influenced Hernandez’s life. However, a majority of the show is also spent with the athlete grappling with his sexuality. The first three episodes include scenes of Aaron (played by Josh Rivera) hooking up with a high school teammate in secret, cruising for guys in the University of Florida library, and panicking that his father, girlfriend, or teammates may find out he’s “gay.” There are multiple locker room scenes where naked male bodies are on display. There’s even a sequence where Aaron looks a bit too long at a teammate’s penis in the locker room—a loose parallel to a moment in Monsters, in which a fully nude Erik makes eyes at fellow inmate Tony in the shower.

In the era of “Hot Dahmer” fan cams, where the scene could be taken out of context and added to all the other homoerotic shots of the brothers, we have to ask if any of those scenes were necessary to depict a holistic version of these real people.

As a viewer who went into Sports Story knowing nothing about Hernandez’s life, I was surprised to find out after watching advanced screeners of the season that his sexuality wasn’t a factor at all in the real-life murder case. There were rumors and an infamous Newsweek piece claiming that Hernandez slept with men around the time of his 2017 death, but the Boston Globe’s 2018 Spotlight investigative series on the case (which Sports Story is based on) didn’t report on the rumors, as they “had not been able to verify that they are based in fact.” It wasn’t until a year later that the Globe found enough evidence to report on Hernandez’s past homosexual relationships, as well as his claims of childhood sexual abuse. In hindsight, it’s been theorized (as alluded to in Sports Story) that Hernandez’s closeted sexuality factored into his trauma and inherently contributed to what could have led him to kill Odin Lloyd. But it also could be argued that Aaron’s sexuality was only a minor factor compared to the entitlement he gained after Florida’s football program continuously swept his bad behavior under the rug to keep him on the field, not to mention his severe posthumous diagnosis of CTE and brain damage (causing violent behavior and poor decision making). After all, the show is Sports Story. What’s the cause of prioritizing Aaron’s sexuality over examining the ways his football success changed his life, for better or for worse?

Aaron Hernandez’s (Josh Rivera) sexuality wasn’t part of his murder trial, but his experience of being in the closet is a major storyline in American Sports Story.

(Image credit: Eric Liebowitz/FX)

American Sports Story at least presents its exploration of Hernandez’s private life through an objective lens; Monsters, on the other hand, turns its depiction of real people’s hidden lives into an obscene puppet show. In the wake of Monsters’ premiere—the series was written by Murphy, co-creator Ian Brennan, and David McMillan— it has been criticized for several scenes featuring homoerotic subtext between Erik and Lyle Menendez. Viewers are going as far as to call the show “incestuous fanfiction,” and even Erik Menendez himself has declared it “vile and appalling.” On my first watch, I quickly felt sickened by how the “monsters,” teenage Erik and Lyle, are sexualized. The first episode includes a sequence of José and Kitty’s memorial that gives way to a sun-kissed montage of Erik working out in little clothing, glistening with sweat—and that’s hardly the first time shots unnecessarily linger on their bodies. Actors Cooper Koch and Nicholas Chavez’s bodies are on display throughout the series, through various shower shots, montages of them enjoying their lives as post-murder, in speedos, and Erik’s Calvin Klein-esque underwear modeling shoot.

It’s a fact that Lyle and Erik Menendez were conventionally attractive, rich, popular, white men and that their trial was sensationalized because that’s the opposite of American media and society’s idea of a murderer (or a trauma victim). In trying to make the point that Lyle and Erik are conflicted, dissonant figures, Monsters switches between two caricatures, making them entitled, asshole, all-American sex gods in one breath and weeping children in the other. On a stronger show, this could make a point about the brothers’ public personas, but on Monsters, the aggressive beefcake angle overshadows any hint of nuance, especially in the show’s controversial, fictionalized shower scene.

In interviews, Murphy and Brennan have compared the show to Rashōmon, the acclaimed 1950 Akira Kurosawa film that tells a murder through multiple points of view. In doing so, Monsters includes different stagings of what could’ve happened during the night of the murders. Its most polarizing scene, where Kitty catches Erik and Lyle taking a shower together, is presented as Vanity Fair writer Dominick Dunne’s theory on why they really murdered their parents. The author of the definitive book on the Menendez trial, Robert Rand, has told The Hollywood Reporter that the incest scenario was “pure fantasy” on Dunne’s part and that the only proven sexual contact between Erik and Lyle was a “response to trauma.” But even in the show’s Rashōmon framing, it’s hard to argue that the show can be billed as true-crime when it makes a point of including something that’s well-documented fiction. In the era of “Hot Dahmer” fan cams, where the scene could be taken out of context and added to all the other homoerotic shots of the brothers, we have to ask if any of those scenes were necessary to depict a holistic version of these real people.

Lyle (Nicholas Chavez) and Erik’s (Cooper Koch) sun-kissed, shirtless bodies are often showcased in Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story.

(Image credit: Miles Crist/Netflix)

In response to questions about the Monsters backlash, Murphy argued the show’s presentation of all the different theories on the Menendezes, even Dunne’s, was a critical part of telling the brothers’ story. “What the show is doing is presenting the points of view and theories from so many people who were involved in the case,” Murphy told Entertainment Tonight. “We had an obligation to show all of that, and we did.” But my question to the show creator: Was there an obligation to include hearsay about the killers that never even made it into the court cases? Whether the shower scene is a theory or not, its inclusion means that Monsters dedicates a portion of its runtime to stigmatizing two alleged survivors of abuse as closeted, incestuous, cold-blooded killers. It’s offensive to real-life trauma survivors and their loved ones, and it’s a literal worst nightmare for any viewers who could be survivors of abuse themselves, seeing this depiction and fearing that if they went public, their lives would be cruelly bastardized and sensationalized for all of Netflix to see.

Sports Story and Monsters aren’t even the first Murphy-verse shows to center on killers, homosexuality, and child abuse. American Crime Story: The Assassination of Gianni Versace included an origins episode that explored Andrew Cunanan’s childhood and implied that the future killer was sexually abused by his father Modesto. (In a 2018 piece, Vulture couldn’t find evidence of the abuse besides one unconfirmed report.) In season 3 of the trailblazing series Pose, Pray Tell confronts his mother Charlene about the abuse he suffered at the hands of her second husband, his stepfather (a storyline that contained similarities to actor Billy Porter’s real experiences of childhood abuse). These stories are important, as they can help illuminate predatory behaviors and inspire victims to seek help or justice, but that doesn’t excuse them from criticism of their handling. Television has only recently grown beyond the negative trope that gay men and other queer characters are inherently nefarious, and a portion of America still believes in those outdated, prejudiced views. In the case of Hernandez, the Menendezes, and Cunanan, when do these stories of children experiencing abuse who grow up to be killers cross over from illuminating into stereotyping?

Murphy’s shows have leaned on sensationalism, camp, and the old Hollywood adage of “sex sells.” At their best, Murphy-verse shows juxtapose the camp with poignant and edifying character studies, like the revolutionary characters of Kurt Hummel from Glee and the entire cast of Pose. Even if Murphy-verse characters aren’t iconic, they’ve often been nuanced vehicles for many actors’ award-winning performances (see Sterling K. Brown in American Crime Story: The People vs. O.J. Simpson, Darren Criss in American Crime Story: The Assassination of Gianni Versace, Niecy Nash in Monster, and perhaps even Cooper Koch in Monsters one year from now). But stories based on real-life people have a much higher duty of care, whether the true-crime genre wants to acknowledge that or not. If done wrong, these series can be exploitative, retraumatizing reminders of people’s worst life experiences or lost loved ones, retold over and over and eventually made into the most popular TV show in the world. Sex may sell, but is there a point where it should be taken off the shelf?